This post includes descriptions of post-traumatic stress.

In this interview, WWDA staff member Mali Hermans spoke with proud queer disabled artist Larissa MacFarlane, one of the WWDA LEAD Art Prize Judges.

As we approach the WWDA LEAD Art Prize Awards Ceremony, this interview is the second in a series highlighting the art of disabled women and non-binary people across Australia. Make sure to register for your free ticket to the Awards Ceremony, and to vote in the People’s Choice Awards!

***

Mali Hermans (MH): First, can you tell me a bit about who you are and your work?

Larissa MacFarlane (LM): Hello! I am a visual artist and disability activist based in Naarm/Melbourne, on the lands of the Kulin Nation. I work across printmaking, street art and a community art practice. I identify as a proud queer disabled artist (she/they) and use my experience of a 22-year-old brain injury to investigate Disabled culture, community, identity, and pride. My visual arts practice began after a brain injury at 29 rearranged my talents. Twelve years after acquiring my disability, I finally completed a Diploma in Visual Arts (CAE). I have now been exhibiting in galleries and streets across Victoria and nationally/internationally through Print Exchanges for over 15 years. My street art often investigates my daily ritual of performing handstands, a key part of my disability self-management and now a symbol of disability pride.

For almost two decades, I have been active in the self-advocacy and Disability Justice movements, leading and collaborating on many community and arts projects. A recent highlight was leading the creation of ABI Wise, the world’s first app made by and for people with brain injury. Another big personal artistic/activist feat was leading Australia’s first Disability Pride mural in 2017 and then producing several more. I currently sit on the Board of Arts Access Australia, as well as on several disability/arts advisory committees, and occasionally deliver arts workshops and self-advocacy training.

MH: When did you first start making art? Why is art an important medium for you?

LM: I first started making art after I acquired my brain injury at 29. Interestingly, I had had no interest or inclination to make visual art before that. I had been a musician but following my ABI, I lost the ability to understand music. Instead, what I could see suddenly became quite fascinating and I was compelled to attempt to draw and paint my new world. It took many years to gain the skills to do this. Visual art is also a way for me to communicate, to work through my new feelings and ideas, as well as explore my new identity. The process of art-making also brings me some calmness amidst the chaos of living with post-traumatic stress and chronic illness. Lastly, art has become a way to connect with others and to chip away at the isolation that frequently comes with disability.

A photo of Larissa smiling and doing a handstand against a brick wall. She is wearing colourful pink and blue clothing, and has her walking stick leaning on the wall next to her. Painted on the wall is an artwork of Larissa doing a handstand!

Image credit: Larissa MacFarlane

MH: Do you think your experiences of disability provide you with a particular lens or insight that non-disabled artists don’t have?

LM: Absolutely! I experience the world very differently as a disabled person. And this difference is of great interest to me. For example, today, I am very interested in the ways that ableism pervades our culture, and the ways that this affects how we think about ourselves. This was certainly not apparent to me before I was disabled. I am interested in finding ways to challenge such ableism and make it visible to dominant Australian culture. And I am especially interested in challenging the ways that we, as disabled people internalise this ableism which further operates to make us invisible.

MH: Are there other experiences, whether they be of race, of gender, of class, that influence your work? How do these experiences interact with disability for you?

LM: I am also a feminist, so I am influenced by the ways that disabled women experience sexism alongside ableism. I am grateful for the knowledge I have gained through the work I do with Women with Disabilities Victoria (WDV). I am also queer, which further influences my understanding of the world, and also influences my work. By connecting with the disability community, I have also been able to embrace the principles of Disability Justice. This has given me greater understanding of how ableism operates in conjunction with the white supremacy of colonialism and capitalism. Living in so called Australia, I am acutely aware that I am a white settler on stolen land, and that First Nations people experience disability at a far greater rate due to forces of racism and colonialism.

MH: Can you share with us a piece of creative work you’re really proud of?

LM: I am pretty proud of all my creative work. In fact, I see all creations as my children, and each one marks a moment in my ongoing development as a proud disabled artist. None of it is perfect and instead is like an unfolding story.

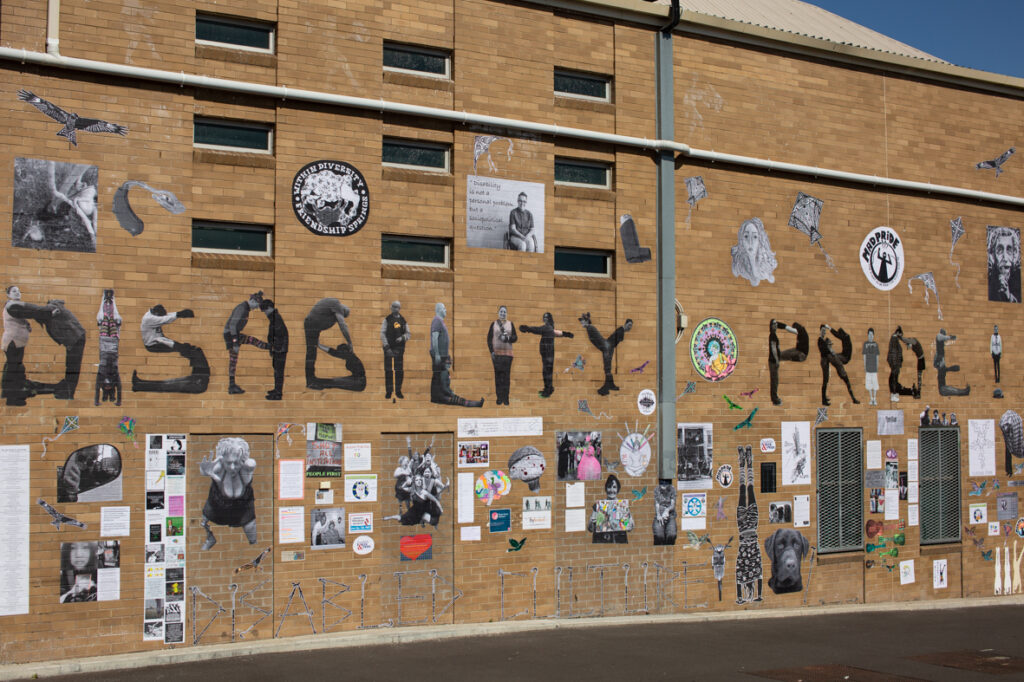

But I guess that one important work to share with you is the Disability Pride Mural of 2017/2018. This is a project where I invited/worked with about 50 disabled people and artists, to create artwork on the theme of disability culture and pride. I then led a day long paste up party, where we collectively installed the artworks on a large Footscray building in Naarm. We believe that this is the first Disability Pride mural in Australia…and maybe the world.

Very sadly, this mural was completely destroyed, only a week later on International Day of People with Disability (IDPWD). It was later revealed to be a mistake by local council. It was rather a big shock to many of us. But somehow, despite much ableism, we managed to recreate the mural, only bigger and better. It still stands today, almost 3 years later, although very faded. When we get through current COVID shit, I hope to start work on developing a new plan for this building. Meanwhile, I have co-authored a short book about the mural, which we hope to release later this year.

Photo of Disability Pride Mural on a large Footscray building in Naarm. It features many different pasteups on a brick wall, including the text ‘Disability Pride’ spelt out using images of different disabled people contorting to make the shape of letters.

Image credit: Larissa MacFarlane

MH: What needs to change in the creative world for disabled artists? What does access done well look like?

LM: A lot needs to change! Just one of the changes I would like to see, is disability arts being recognised within contemporary art. At the moment, it mostly exists outside the ‘art world’ as something other and not relevant to contemporary Australia. This impacts on the ability of disabled artists to access art experiences including education as well as earn income from their art.

Access done well encourages open and kind conversations about accessibility and ableism. This approach gives us space to unpack the limiting and stereotyped ways that we generally think about disability.

MH: Finally, what is one piece of advice or encouragement every disabled artist should hear?

LM: Make the work you want to make and make work that interests you. Ignore the messages and attitudes that say that art must be done a particular way. When I finally got to art school and met other artists, there were strong messages that if wanted to ‘make it’ as a contemporary artist, then I needed to remove any reference to my brain injury from my artist bio. Fortunately, even though I did try to do this for a time, it was impossible given that it is my ABI that has given me this gift of art.

I think it is also important to understand that disability is complex and ever changing, and we are not static one-dimensional people. This means that disabled art is still an exciting frontier with much to explore. Let this give you comfort and courage.

Other advice (that I try to give myself daily) is that the work that we make as disabled artists may not yet be valued or understood by contemporary culture. But that doesn’t reflect on the value or strength of the work that we make. We just need to keep making it. And through the making of our art, we become stronger as both people and as artists.